I’m taking this week’s main message from an entry to our internal log that I penned last weekend (adapted/edited to be featured herein).

Again, the following will not inspire the reader to back up the truck to the stock market, unless, that is, to perhaps empty it, but make no mistake, as you’ll also gather below, with clarity comes opportunity!

If I had to pick one overriding long-term macro theme to focus on going forward it would be the fact that OECD countries plus China possess very poor demographics, making for tough general conditions for years to come…

As for the moment:

Essentially, the world economy has become for the most part a planned economy. The price discovery mechanism in debt markets (Greece 10-year sovereign debt fetches nearly what 10-year treasuries fetch [unbelievable!]) has been severely hamstrung, if not gone altogether. The impact of the Fed’s foray into corporate bonds has tightened credit spreads (the difference in yield between riskier corporate bonds and safe treasury bonds) to levels that would have signaled, pre-March 2020, that all’s well in the U.S. economy. Well, 11 million folks on unemployment, and record corporate bankruptcies and bond defaults, suggest otherwise…

Central bank digital currencies appear to be on the horizon… That’ll pave the way for further monetary reform… a topic for another day for sure…

Deglobalization/populism is the growing global theme… Protectionist policies, immigration controls, etc., will serve to exacerbate demographic headwinds, and, should present trends persist, dangerous geopolitical risks will continue to heighten…

In the meantime, huge government spending along with ultra-easy monetary policy will, ironically, provide some level of support for global stock markets…

Real assets — post recession — are likely to outperform for years going forward…

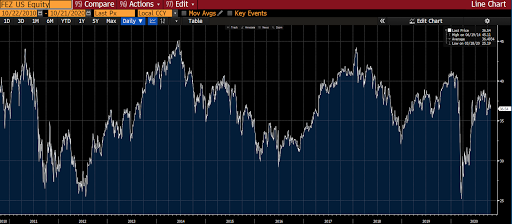

Short-term forecasting is exceedingly difficult these days as securities markets rest at historically-high valuations amid exceedingly weak fundamentals, while, via government and central bank intervention, there’s ample liquidity to push prices higher on headlines. I.e., presently, liquidity and momentum rule, fundamentals simply do not matter… Historically-speaking, that’s toppy phenomena…

A mood shift — introducing the hoard of inexperienced traders to declining share and options prices — from these high and concentrated levels could easily gain momentum and ultimately see equities, at a minimum, testing the March 23rd low in the not too distant future. Present sentiment and market structures/internals smack of the conditions that led to similar events past…

Longer-term, commodities and dividend-paying large cap equities in developed markets, along with emerging market equities (where demographics are favorable), will likely dominate our portfolio exposures. Over the next year+ infrastructure-related equities will be an area we’ll no doubt be looking to exploit…

Bonds have enjoyed a multi-year secular bull market that has, virtually by definition (record low interest rates), ended. Risk is clearly to the downside (yields higher), however, central banks will bring much to bear to mitigate what is huge risk going forward. That said, we will seek out safe opportunities in areas such as very short-duration investment grade corporates to gain better than money market yields on our core fixed income allocation.

In summary:

“Capitalism is based on individual initiative and favors market mechanisms over government intervention, while socialism is based on government planning and limitations on private control of resources.” — Investopedia

Any narrative that supports rising inflation going forward flies in the face of burdensome demographics, extreme debt levels, present political and geopolitical trends, etc. — as those are all arguably deflationary phenomena. Thing is, we are about to experience an utterly massive government spending campaign (arguably inflationary), plus, there’s what they call stagflation — inflation that occurs during a period of economic malaise. I.e., stagflation has more to do with capacity constraints (I know, there’s that “output gap”) than it does growing demand, and higher interest rates under such circumstances has much to do with the need to issue debt (again, the US govt is now 40% of GDP) that exceeds the market’s capacity/willingness to absorb it (at record low interest rates, that is). Of course the Fed has a plan for the latter.