I’m reading lots of commentary these days from macro players who still see the bond market as a legitimate signal of general conditions.

They tend to also see inflation right here as transitory phenomena; believing that once covid-driven bottlenecks are relieved we’ll see the costs of goods and services descend to notably lower levels, and/or we’ll see the future rate of inflation slow, and meet right back down with that sub-2% trend.

As I’ve expressed herein aplenty, while we remain open to all possibilities, the above — for a variety of reasons — is not our longer-term base case.

Here’s a snippet from our own inflation narrative:

“…amid what may be a period of relatively low velocity of money, heavy debt burdens, and, we presume, further technological advancement — I nevertheless see increasing odds that we’re at long last on the cusp of something meaningful (but not 1970s meaningful, mind you) with regard to structural inflation risk:

- Increasing populism (a serious headwind for global trade — in both goods and in labor).

- A continual stimulating of the economy via fiscal policy (facilitated by easy monetary policy) — demanded by a politically-powerful populist movement.

- China maturing into a service-oriented, consumer-driven economy (while moving away from providing cheap labor and goods to the outside world).

- The Fed’s fear of bursting present asset and debt bubbles were it to implement traditional inflation-fighting measures — thus willing to fall notably behind the inflation curve well into the foreseeable future. In fact, I personally place better than 50/50 odds that if indeed a long-term trend of rising inflation emerges, that the Fed will revert to yield curve control (buying up the price (down the yield) of longer-term treasuries) to cap lending rates that, were they allowed to rise, would themselves produce a headwind to rising inflation.

- The trillions of dollar-denominated debt sitting on foreign corporate balance sheets inspiring an active campaign by the Fed (read multiple foreign currency swap lines) to keep the dollar at bay, in an effort to avert what could otherwise turn into a very messy global currency crises.

- The reticence of producers in the metals space to aggressively expand capacity despite rising prices: Speaks to the devastation they experienced post the 2000’s China building boom.

- The political/environmental headwinds for fossil fuel producers to expand capacity.

- Inflation being the US’s historically-preferred mechanism to reduce heavy federal debt burdens.

Now, all that said, before we settle into that structurally rising inflation scenario (if indeed that’s where we’re headed), I look for a notable calming of the thrust we’re presently experiencing — as the worst of the production bottlenecks subside — inspiring a chorus of I-TOLD-YOU-SOs from the “it’s transitory” camp.”

Note: Can’t help but point out (with regard to the second-to-last bullet point) that Washington just went knocking on OPEC’s door asking them to please increase production! Oh the irony…

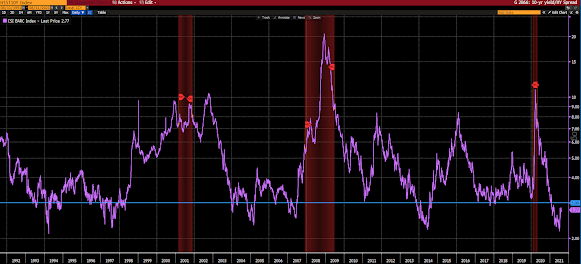

Starting with the high yield spread (CSI BARC Index [10-yr junk bond yield minus 10-year treasury yield]):

Notice that a sub-3% (blue line) spread never (over the past 20 years) occurs during times of heightened economic stress (recessions in red), quite the opposite, in fact.

As for the spikes that occurred outside (or not within close proximity) of recessions, there were indeed causal factors to point to:

And here’s the 10-year treasury yield (note the negative correlation to the high yield spread):

Now, to be fair, one could argue that it’s not about the level, it’s about the direction, and the rate of change. In which case, the chart of the past 2 years (below) doesn’t look all that unusual. That negative correlation, save for a stretch here and there has remained pretty much intact:

The Fed’s objective being to keep asset and debt bubbles from popping under the weight of tight(er) conditions, and, as a result, to allow inflation to ultimately take the government debt-to-GDP ratio to a level notably below 100%.

The trillion(s) dollar question of course being, will they achieve their objective?

“The problem with a speculative bubble is that you can’t make the short-term outcomes better without making the long-term outcomes worse, and you can’t make the long-term outcomes better without making the short-term outcomes worse. Now it’s just an unfortunate situation.” –John Hussman